Artwork 8: Guernica

While the Picasso Century exhibition is on in Melbourne, let's look at the bloke's most famous artwork.

The voice of a generation?

Shortly after Picasso’s death in 1973 a critic wrote that ‘history will record, if only because of the works of his Blue Period, and a few later paintings, like Guernica, that he was a great artist.’1 And this critic seems to have been right. Not many twentieth century artists have such a descriptor applied to them as often. I’m curious, though, about the how a single painting such as Guernica, could attract such fame, let alone it's creator.

The same critic, Terrence Mullaly, noted that ‘even if in a monumental painting such as his Guernica produced in 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, the element of the grotesque is dominant, the power of such a work is patent. Guernica, in particular became a symbol for a generation.’ While the power a viewer sees in a work might be highly idiosyncratic and subjective, the way this painting became a symbol can be traced through time. Well, I hope it can because that is the aim of this issue of the newsletter, prompted in part by ‘The Picasso Century’ exhibition currently on at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne and partly by the war in Ukraine.

Guernica is composed of a dis-jointed group of animals and humans in extreme distress. Faces are turned upwards and outwards in terror and despair. Sharp jagged shapes describe a mother with lifeless baby. A bull, a horse and figures with arms raised or outstretched contort under a bright bulb of jagged light.

The gathering of despairing figures appears to take place in a darkened room. Doorways and walls frame the action and give the impression of a loud and cramped interior. Knowing that the painting was Picasso’s commissioned response to the bombing of the town of the same name, a town in the region his father grew up in, suggests the blitzkrieg is happening above the figures and that the dwelling itself resembles a haven of childhood, destroyed indiscriminately.

The town of Guernica was a centre of Basque cultural and religious identity when it was bombed. Of no military value, its destruction by the German air force, supporting the fascist Nationalist Generalissimo Francisco Franco, was intended to shock the Basque population into submission. High explosives and incendiary bombs were dropped on the village for three hours, an unprecedented use of force at the time.

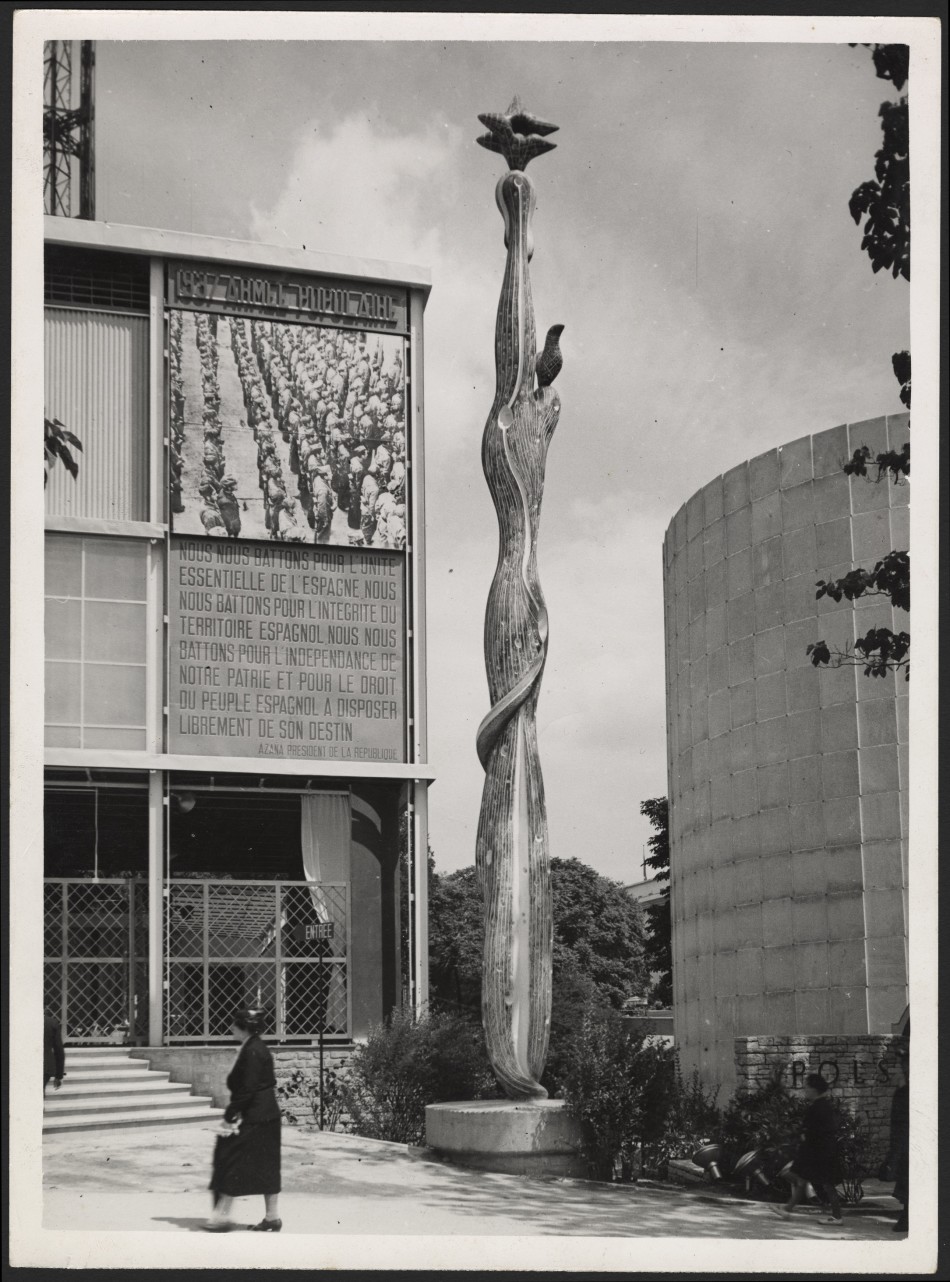

Picasso was asked by the Spanish Republican government to contribute something to their pavilion at the 1937 Paris World’s fair. This was six months into the military revolt undertaken by the Nationalists against the Republican government and involved a host of architects and artists working to produce a building which encapsulated their cause. Opposite Guernica was American artist Alexander Calder’s Mercury Fountain and in the forecourt downstairs stood the 12m tall sculpture El pueblo español tiene un camino que conduce a una Estrella, The Spanish People Have a Path that Leads to a Star by Alberto Sánchez (pictured below). The façade was covered by photomurals designed by Josep Renau presenting the traditional dress, industries and topography of the various regions of Spain.

The pavilion’s designers were Josep Lluís Sert and Luis Lacasa. Sert was a disciple of influential modernist architect Le Corbusier, memorable for minimalist architecture that disdained decoration in favour of practical, modern and useful design. I remember Corbu (as Le Corbusier is sometimes known) as the guy who said the house was a machine for living in (at a time when a statement like this was utopian, rather than dystopian). Modernist designers like Corbu, Sert and Lacasa believed in the power of design to change people’s lives, to improve society as a whole. (As ideas go it was an oldie but a goodie, just ask Vitruvius). This did not always go according to plan, however, and the criticisms he faced should probably be noted by the folks in Silicon Valley…

At any rate, Sert and Lacasa envisaged the building to be clearly ‘rationalist and supremely functional in concept’, and like Le Corbusier they used prefabricated elements. The pavilion had three storeys linked by a stairway or side ramps (minimalist moderns loved a ramp). The main feature has been described as the building’s ‘fluidity and transparency’, which isn’t easy to achieve in concrete, crystal and glass. Though it looks grid-like, the spaces are open and almost every surface has been thought of as something on which to display Spain’s culture and the horrors of the civil war. A replica was created in 1992.

After Guernica went on display at the Paris world’s fair in 1937, it toured throughout Scandinavia and England, and it was during these travels that its association with anti-fascism was cemented. Explicitly linked to the cause, Picasso stipulated that the painting could not be displayed in Spain while Franco ruled. Unfortunately the Nationalists won the war which ended in 1939 and ruled Spain until Franco’s death in 1975, and it wasn’t until 1981 that the painting was displayed in the Prado as requested. The reputations of both the painting and the artist grew through this exile.

While on display in America, Picasso tapped into the support of a philanthropically motivated art world. Among the excellent online archive about Guernica from the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte, Reina Sofia, is a letter from the wives of two wealthy businessmen (Simon Guggenheim and Dana C Backus), seeking donations for a fund to support Spanish refugees, specifically intellectuals, on Picasso’s behalf. Louise Laidlaw Backus and Olga H Guggenheim wrote that “Picasso is very enthusiastic about the Guernica exhibit now on view at the Valentine Gallery and has asked the Committee to prepare a scrapbook of clippings for him.” They also asked for a financial contribution and for supporters to sign the enclosed card which would also be sent to the artist. I think we can glimpse Picasso’s savviness here, not only seeking to document the journey of the mural but using wealthy allies in NY to use their wealthy ally networks. This type of soft power tactic aligned with the US government’s non-Interventionist policy.

After a successful tour, the painting went on display in New York. Its status as an anti-war statement was by then firmly established. As new conflicts arose and the Spanish Civil War was overshadowed by fascism in the Second World War, Guernica took on a new life. Here are two examples.

Anti-War in Vietnam posters

In 1970 the Arts Workers’ Coalition at the Museum of Modern Art New York distributed a petition to “curators, trustees, etc” throughout the country. It read:

Our nation is presently engaged in a war in Southeast Asia, which has world-wide implications, and which at home threatens to tear our very social fibre. The following statement is an expression of our concern as human being, who can no longer just sit by and witness a war that kills our boys and their boys. As members of institutions which glorify life and harmony amongst all men, we feel it our duty to speak out against the war and especially the roots of war.

We resolve: that the most pressing cultural and national issues of our time are racism, sexism and repression. The war in Southeast Asia is the most blatant manifestation of these crises. Therefore, we demand the immediate withdrawal of all U.S. Military involvement in Southeast Asia.

Protest banners from 1967 utilised a segment from Guernica, showing the decapitated head with outstretched arm. Its text read: STOP THE WAR IN VIETNAM NOW!

Reading art critic and anti-war activist Max Kosloff it’s hard not to apply his sentiment to today:

“To write of art and politics in the United States in 1967 is surely to court futility in a context of provocation. And yet, to ignore the subject in print (however much it may prey privately on the mind) is to repress an urgency that makes the misgivings of an art critic almost weasel-like… There is nothing like a national crisis—and the war in Vietnam is a crisis raised to the pitch of horror—to make aesthetic pursuits look pitifully insignificant. But there is also nothing like such a crisis to cause some of us to rethink the nature of our role as men involved or concerned with creativity.”

The Security Council Tapestry

In 1955 Nelson A Rockefeller, wealthy politician and art collector, and cog in the Cold War propaganda machine, commissioned a tapestry reproduction. He had many reproductions of Picasso’s work among his collection, but as you’d expect, none was as captivating or as famous as Guernica. So much so that it stood in for the real thing when the original could not tour.2 It hangs in the UN Security Council, some argue as a reminder that the organisation has its foundations in the defeat of fascism, others note that it commemorates Rockefeller’s aid in constructing the UN headquarters.3 In 1985, his widow Happy Rockefeller loaned the tapestry, long term, to the UN and this is where is has remained with the exception of a mysterious recent absence.

The power of Guernica’s anti-war message was vividly confirmed when, on 5 Feb 2003, Secretary of State Colin Powell stood before it to make his pitch for the US war in Iraq. However, that day the tapestry was hidden underneath a blue curtain. Rumours that the US leaned on Security Council staff to have the painting covered were circulating. Officially, the story went that this blue curtain presented a neutral backdrop and nothing more. David Walsh, writing for WSWS.org wrote at the time:

Aside from its general evocation of anti-war sentiment, Picasso’s painting threatened to speak to historical parallels that the Bush administration and UN officials were clearly determined that the media or the public should not make.

Guernica’s message could not be censored, though, as protestors gathered outside the building holding copies of the painting while Powell made his appeal for war.

Rockefeller’s association with Guernica, art historian KLH Wells has argued, has more to do with his own politics, than his desire to support Picasso’s communist commitments. As a capitalist who supported American interventions abroad, Rockefeller’s motivations must have been as an art collector first. Wells covers some really interesting ground about the tapestry being both a copy and in a format traditionally used to signal royalty and status. To have an entire art collection in tapestry form was a bit of a power move, which allowed Rockefeller to ‘own’ prized pieces and in a format associated with kings.4

More than a symbol for a generation, Guernica has become synonymous with opposition to war in general. Once a very specific invocation of the horror of the Spanish Civil War, Picasso’s mural has surpassed its origins and now functions as symbol seemingly universally applied. The example here though, relate more to the history of America’s fascination with and use of the mural in different contexts. (If I were an anti-war hippie protesting in the 70s you can bet I’d be holding a section of the painting as a protest sign. Same for the anti-Iraq war protests, were I old enough!) It would be equally interesting to hear whether Guernica has reached similar levels of symbolism in other parts of the world.

My response, as always has been shaped by the sources I have access to. I’ve drawn upon some excellent research and websites for primary sources. (See the links throughout and notes below.)

There is more to say and more to see, always. If you enjoyed reading this edition of Slow Looking, let me know, or suggest an artwork. :)

Terence Mullaly, ‘Picasso, the Giant who Fell Victim to his Own Image’ Daily Telegraph (London) Monday 9 April 1973, 5. ↩

K.L.H. Wells, Rockefeller’s Guernica and the collection of modern copies, Journal of the History of Collections, Volume 27, Issue 2, July 2015, Pages 257–277, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhu029 (open access) ↩

Ibid, p 273. ↩

Ibid. ↩